Welcome to the SPI Comprehensive Guide to Writing and Publishing a Book!

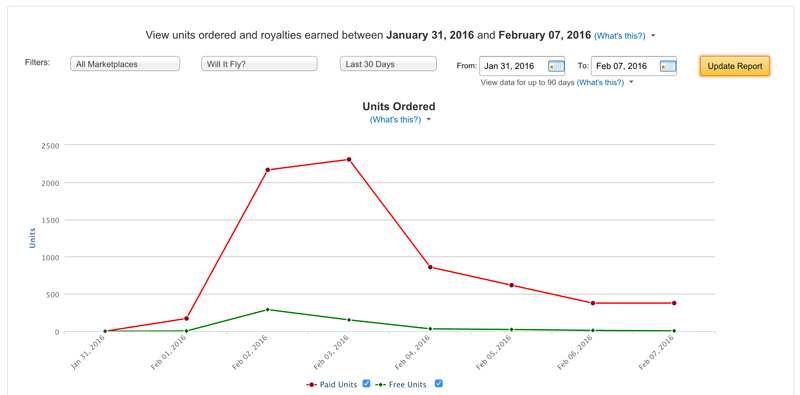

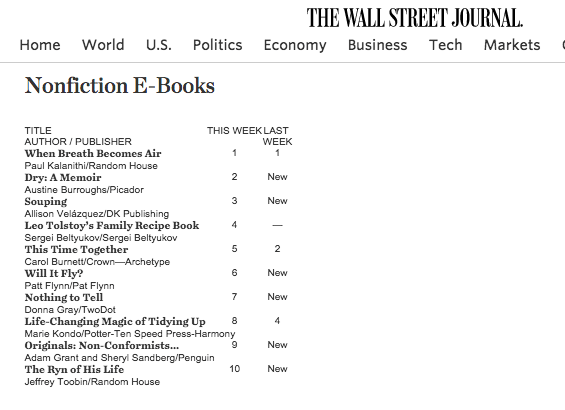

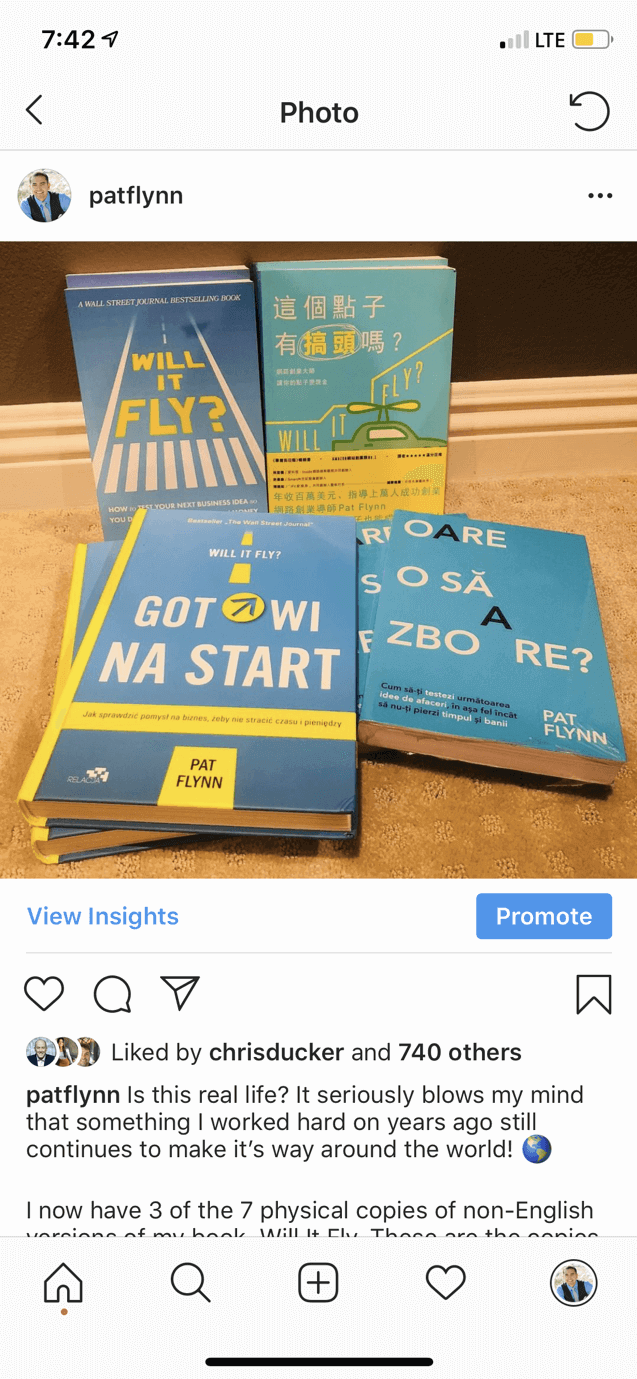

Here at SPI we have supported Pat in self-publishing not one, not two, but three books: Let Go, Will It Fly?, and Superfans. That’s right—as of 2019 all of Pat’s books have been self-published. In addition to supporting Pat’s books, several members of our team have years of industry experience as publishing professionals working as writers, editors, and consultants for other authors on books that have been both self-published and traditionally published. As a team we have made plenty of mistakes, but we’ve also done a lot of things right, landing one of Pat’s books on the Wall Street Journal bestseller list and hitting the number-one bestseller spot in multiple categories on Amazon.

All that to say, a lot of collective experience has gone into gathering the best information on writing and publishing a book that we can and compiling it in one place. Our goal with the SPI Comprehensive Guide to Writing & Publishing Your Book is to make it super easy for you to find what you need depending on where you are with your book and what type of publishing you’d like to pursue.

This epic guide, and the others that we publish here on SPI, is our way of sharing the knowledge and experience we have gained in book publishing directly with you, for free. Why? Because we know how valuable it is for you and your brand to have a published book with your name on it as the author. And if publishing a book is something you’ve been thinking about doing, we want to help you accomplish that goal, for your sake and the sake of the people you serve with your business.

One of our core values here at SPI is to pay forward what we’ve learned. So let’s get right into it with you, your book, and getting it published for your audience to actually read!

Let’s start with one question, and perhaps the most important one to ask . . .

What Is the Benefit of Writing and Publishing a Book?

If you’ve been in the online business space for even a short amount of time, you’ve probably heard someone say that the best way to spread an idea or message is with a book. And it’s true. Imagine that a prospective client or customer lands on your website for the first time and they are trying to navigate through your massive content archive to find out what you’re all about.

Now imagine that you had a book that neatly packages and organizes your core message in a way that is meant to resonate with your exact target audience. It’s the most essential stuff all in one place, and can be read in a relatively short amount of time.

Speaking of the most essential stuff, writing a book forces you to get clear on your message because you can’t include everything, and you have to make decisions about what to include and what to edit out. It’s no easy task, and when it’s done it demonstrates your fortitude and dedication to honing what you want to say, actually writing it, and seeing a huge project through to the end. You may have done this in other areas of your life, especially in your business, but how can you showcase that work that’s so often behind the scenes? A book is a visible, tangible way to tell your story, one that will continue to live on the shelf even long after it’s been read.

A book is also a way to establish yourself as an authority in your field or niche. It used to be that only the experts (famous people with big accomplishments) or established writers had access to getting published and were invited to write books. That is no longer the case in the twenty-first century, but there is still an association of authority that is inherent with being an author—if someone has written a book, then they must know what they are talking about.

Lastly, what about the benefit of making money from a book? Yes, a book can absolutely be a new revenue stream for your business. That said, in our experience the goal of making money from a book shouldn’t be the only reason to write and publish one—a book can definitely drive revenue, but you have to remember that the revenue it drives will likely be more than strictly sales of the book itself. The book will be building brand awareness, getting people to know, like, and trust you, and even promote your business philosophy or service. Once people are familiar with you because of your book, they are more likely to spend money with you for your other products or services.

What to Expect in this Epic Guide to Self Publishing

Many aspiring authors get overwhelmed just thinking about writing a book and never take action. This is completely understandable—writing and publishing a book is a huge undertaking. There are a lot of steps, a lot of moving parts, and it’s not something that can be easily done in a month or two (not unless it’s the only thing you’re working on). We get it, and so we’ve broken this guide down into smaller, manageable components that will help you to also think about your book projects in smaller, manageable pieces.

One last thing before we move on: some of the following chapters are written by Pat about his firsthand experience writing and self-publishing his three books, while others are written by me, Janna Maron (content director for SPI), focusing on processes and options that can be applied regardless of how you choose to approach your own book project. Don’t worry—we’ll always let you know who you’re hearing from in a given chapter.

Now, here’s what we’re going to cover:

- How to Start Writing Your Book for Publishing

- How to Edit Your Book Before Publishing

- How to Get Your Book Manuscript Ready for Publishing

- How to Get Your Book Design Ready for Publishing

- How to Start Publishing Your Book

- 14 Tips for Writing & Self-Publishing Your Book

- How to Start Marketing Your Book

- 9 Tips for Marketing a Self-Published Book

- 12 Tools for Writing & Publishing Your Book

- 8 Book Publishing Mistakes

- Self-Publishing Case Study: A Closer Look at the Numbers Behind 2016 Bestseller Will It Fly?

- Take Your Book Publishing to the Next Level

Get your free Book Publishing Cheat Sheet.

Learn the step-by-step publishing process guidance and get a high-level overview of the 5 stages of publishing. Our cheat cheat sheet covers steps for both ebook and print.

How to Start Writing Your Book for Publishing

So you have a book idea. Now it’s time to actually starting writing your book, which can be quite an undertaking—especially if you’ve never done it before. Here’s Pat with that important question to get us started on how to actually write the book.

Why publish a book in the first place?

You should never publish a book just because you can, because publishing a book is not an easy task. You should have a clear purpose in mind, not only for the topic of the book, but also for its reason to exist in relation to your brand and your overall goals.

The best way to figure out the purpose of your book is to visualize what it might look like within your brand. Imagine that it’s already published. What would it help you do? Is the book meant for generating leads? Building authority in a niche? Are you publishing it just to make money?

There are a lot of reasons to write and publish a book, but if you’re not clear on what those reasons are for you, you’re going to lose your excitement for it, especially when you get to the tough parts of the writing and the publishing.

If you need help discovering your reasons for writing a book, ask yourself these three questions:

- What is my book about?

- Who is it for?

- What do I want readers to feel or do when they finish my book?

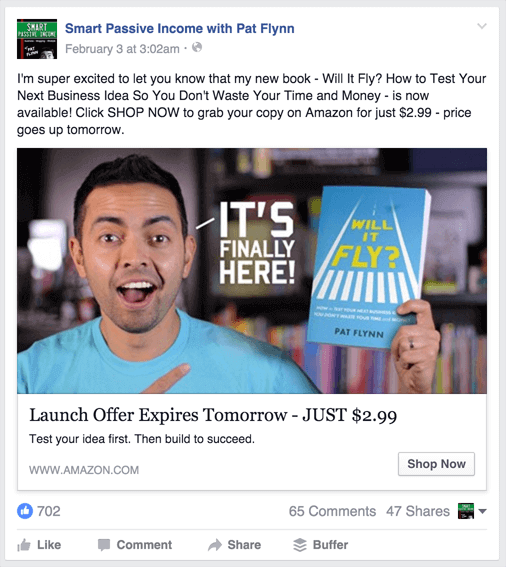

For me, Will It Fly? was not published primarily to make money. For the most part, authors don’t make money directly from their books, although that’s not impossible as Nathan Barry shared in Session 75 of the SPI Podcast.

I wrote and published Will It Fly? for two equally important reasons:

- more exposure

- more control

Let me explain…

More Exposure

If generating the most immediate income from this work was the goal, I would have either sold the book directly on my own site and charged a lot more (à la Nathan Barry), or created an online course instead.

Getting the book in the hands of people who have not yet been exposed to me or the SPI brand was more important to me, and self-publishing a book to use Amazon’s algorithms is the mechanism for doing just that. This is a long-term game plan, and I’m hoping Will It Fly? becomes a great first impression—a pleasant start to a life-long relationship I have with new readers, subscribers, and customers.

More Control

Additionally, since starting SPI, I’d been generating most of my income from affiliate marketing and redirecting people to other people’s stuff. In order to make the most impact, and also keep people interacting with my brand, I had to start creating my own stuff, and it all started with this book. Will It Fly? lead to courses and other SPI branded material, and with that I’m able control the conversation I have with my audience, and the experience they have throughout their business journey.

Control is also part of the reason I wanted to self-publish the book, instead of going with a traditional publisher, despite traditional publishers reaching out and wanting to work with me. As I mentioned in the introduction for this guide, although there are a lot of pros that come with working with a traditional publisher (i.e. an advance and distribution in physical book stores), I would also give up some control over things like creative direction and content. Since most authors end up doing a lot of their own marketing anyway, I knew that self-publishing was the right choice—at least this time around.

With that choice, however, that means it’s more work for me to get everything done and executed properly on my own. But it’s great because I now know how it all works, and I can share what I’ve learned with you.

How to Know What to Write About?

Obviously, the topic of the book you choose to write is an important one. First, you want to write about something that will serve your target audience, of course. Combine that with the knowledge you have and the research you will do, and you’ve got a potential topic for a book.

But an idea alone isn’t enough. Is there a way to validate a book topic before writing it?

Absolutely!

Since Will It Fly? was all about idea validation, I knew I could (in a very meta way) validate the idea of my book before writing it. The idea first came after hearing the same question coming directly from my target audience over and over again. Through emails and voicemails coming from AskPat.com, the number one question people asked was:

“How do I know if the idea I have is one that will pay off?”

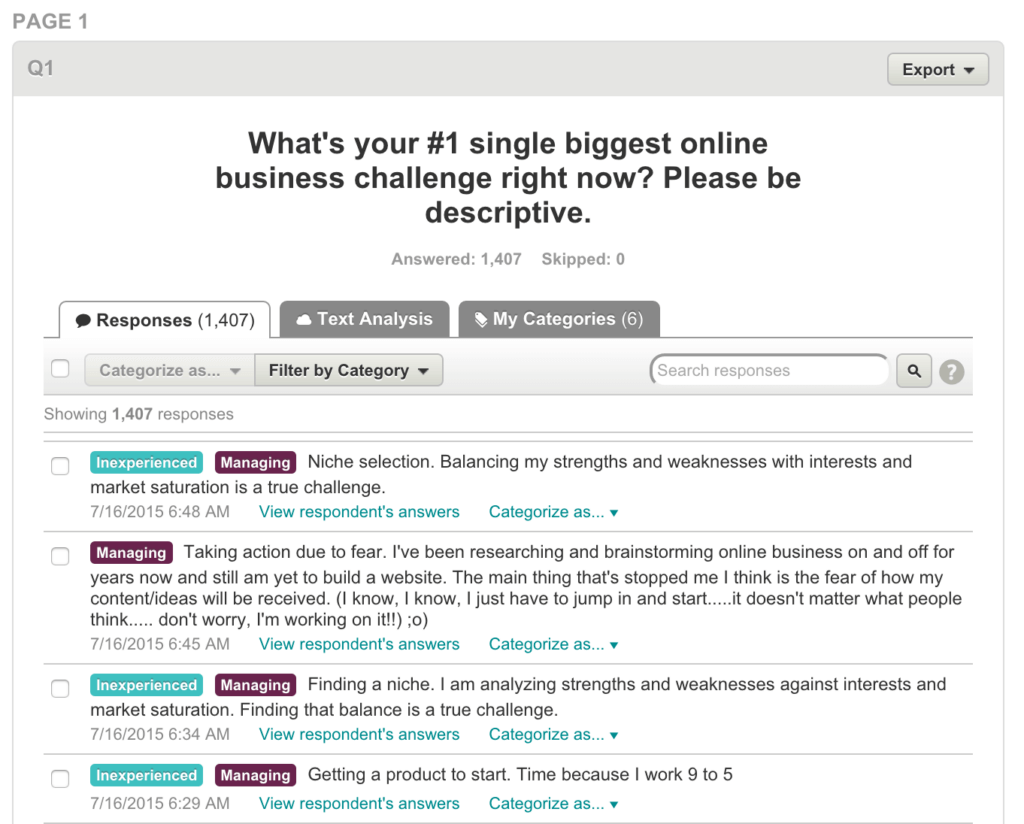

After you all planted this seed in my head and I started to research this topic, I conducted a survey that confirmed this once again. For those answers from people who had yet to start a business, the number one struggle they faced was figuring out what niche to get into, and the fear of something not working out:

Even those who have started a business shared that they struggle with some of the same thoughts around their business idea:

![Answers to survey question, "What's your #1 single biggest online business challenge right now?"

Answer #1: "Sticking with one idea and going at it full throttle."

Answer #2: "Lack of focus and execution."

Answer #3: "Monetizing traffic."

Answer #4: "Driving traffic to my website. Finding where I can go to get traffic. Everyone says do it this way or that way."

Answer #5: "Getting users to click on links and convert visitors into readers into customers, for personal and affiliate sales."

Answer #6: "Getting going. It's possibly having the confident [sic] to put what I've read and heard to use. Will my efforts actually produce anything? Do I have the patience and fortitude to keep with it?"](https://www.smartpassiveincome.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/SPI-business-validation-audience-survey-2-1024x935.png)

After this, it was time to make sure that this was indeed a topic of interest for people, one that they would pay to learn more about.

I reached out to thirty people on my email list, at random, got on a Skype call with them, pitched the idea for the book (being honest that the book wasn’t even finished yet), and I asked them to pay $10 to my PayPal account if they would buy it.

Of the thirty people I reached out to, I was able to speak to about twenty of them, and out of those twenty, ten people paid me money. That’s how I knew the book idea was going to work.

There are other ways to validate a book idea. I haven’t done these myself, but I have seen other authors do these two things with great results:

- Write a guest post about the book topic on another site and gauge the reaction. This is a great approach, especially if you don’t have an audience of your own yet.

- Write a mini-version of the book and give it away for free, potentially turning it into a lead magnet for your email list. See what the reaction is like from there, and then turn it into a published book if people want more. This is what Michael Hyatt did for his book launch for Living Forward, which went on to become a bestseller.

Publishing a book is a big task, so it’s best to spend a little bit of time upfront to make sure it’s something your audience wants to read first.

Time To Write

Now that you have identified your why for writing and publishing a book, and a topic that your audience will want to read, you can’t do anything else until you of course have . . . a book. Book writing is something that used to be a constant struggle for me. Read on to learn about the process I used to write over 36,000 words in the first two weeks of 2015—and that I’ve been using ever since with great success. I’m also going to give you one tool that is saving me so much time and helping me achieve up to 180 words per minute.

A book is such a huge undertaking. It’s really funny, because I can write a blog post—3,000 or 4,000 words—in just a few hours, but when it comes to writing a book, I struggle a lot. That’s why I have a couple unwritten books just sitting on my computer, in Scrivener, which is the tool I use to help write books. It’s a great tool—the reason those books weren’t finished is that because I just couldn’t do it.

I remember sitting for hours. I would block out four or five hours of time during the day, just sit in front of my computer and come out of that with an extra 300 words for four hours of work. It was completely defeating—and I know a lot of you can relate to this. I know a lot of you also, like me, feel you have a book in you—maybe even many books in you. So I’m going to show you a book-writing technique that has changed my life in terms of productivity. I used it to write my book Will It Fly?, and within the first couple of weeks of 2015, I cranked out 36,000 words.

Using Post-It Notes to “Brain-Dump” Your Book’s Topics

I’ve adopted this technique from a lot of other people’s strategies and tips for writing books, and it’s involving something that a lot of other people have used before: Post-it Notes. I love Post-it Notes, because you can write on them and move them around. They’re small, but not so small that you have to squint to see them. So they’re perfect. I’m going to show you how to mind-map your next book using Post-it Notes, and how you can achieve incredible words per minute in terms of the rate at which you write your book.

The first step is to get some Post-it Notes. Make sure to get a bunch of different colors. I like the smaller ones, because you’re just going to write one or two words on them. Then you want to pick a color—and just start writing. Start with anything that comes to mind involving your book, put it down, one idea per Post-it, and stick it to the surface that you’re working on, whether it’s a desk or a whiteboard.

To demonstrate this, I’ll use a sample topic. Something I always talk about on the blog is fly fishing, and it’s something I know a little bit about. Using the example of fly fishing, I’ll show you how I can start to put together my hypothetical book and once you start to put all your ideas onto the board that you’re working on with Post-it Notes, you can move things around. Then the chapters and subchapters start to form, which help to create what becomes your outline.

So, fly fishing. I pick a color and place it in the middle to label my central idea, so I pick a pink note and write “fly fishing” on it. With this process, you write anything that comes to mind; there are no rules here. You can always throw things out, but you don’t want to stop yourself. This is the creative process. You don’t want to edit in your head. You just want to put things out there, and later on you can edit.

I’ve got “fly fishing.” Next, what is involved with fly fishing? I’m brainstorming anything and everything I can think of related to fly fishing and writing each one down on a separate Post-It. Things like:

- Fish

- Flies

- Rods

- Casting techniques

- Reels

Again, write down anything that comes to mind. You want to put the stuff that’s in your brain down on paper, because then you won’t have to think about it anymore. You can focus on organizing later, but we’re not there yet. So what else for fly fishing?

- Lake fishing or lake fly fishing

- Rivers

- Streams

- Oceans

- Tying flies

- Tournaments

Keep asking yourself, what else comes to mind? And usually one topic will spark another.

- How to dry things off after you’re done

- Equipment

- Clothing

- Trout fishing

- Bass fishing

- Fly fishing for kids

- Destination areas

- Where in the water

- Boots

- Safety

- License

- Net

- Catch and release

- Etiquette

- Snacks

- Fish finders

- Wading boots

- Boats

- Floats

- Jackets

I know a little about fly fishing, but I’m not a fly fisherman. You’ll obviously know a little bit more about the topic you’re working on, so you should be able to fill up your work surface pretty easily. When I was writing my last book, the table was completely filled with notes.

You can see the idea here is that there’s no particular order to how the sub-topics emerge, and nothing is off-limits. You just want to get down as much as you can so that you have plenty of ideas to work with. The order and organizing comes next.

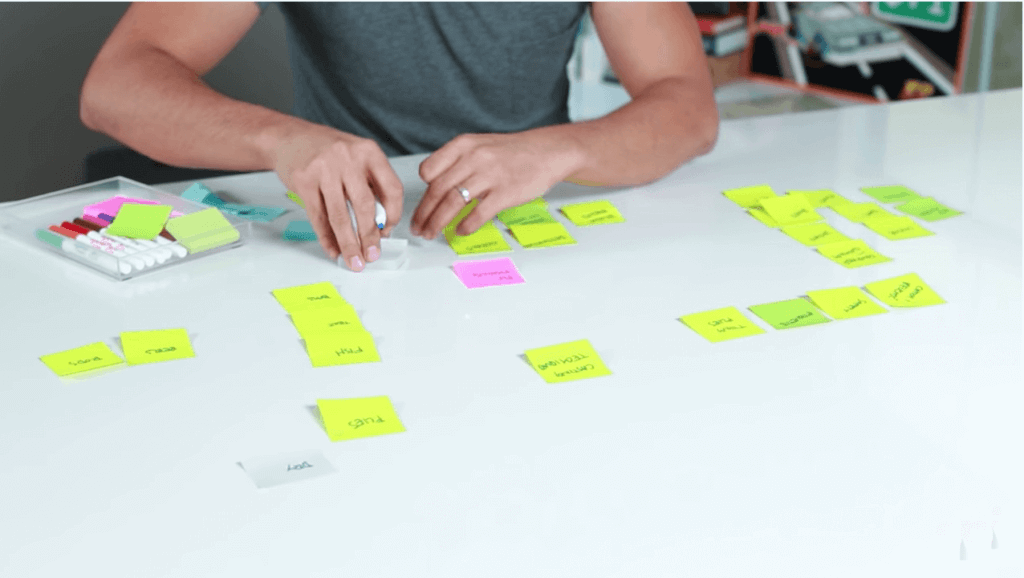

Start to Create Some Order

At this point, you should have a whole board or desk full of Post-it Notes. Next, you want to start looking at all of them so you can start to tie them together. Pull them off and start moving them to different places, organizing them in groups that make sense to you. You’ll see that your brain will just start to organize them. Again, it’s nice that it’s all here for you because then it’s much easier to move things around.

For example, I can put “jackets” and “wading boots” together. “Equipment” and “clothing” are the top-level categories. Then I have “reels” and “rods” and “flies” with equipment. Then I have behavioral topics like “etiquette” and maybe “casting techniques” together. I have “oceans,” “lakes,” and “streams” grouped. “Snacks,” which is something to bring, so maybe that’s grouped with equipment.

“Safety”—I can put that with behavior. “Destinations”—that can go with “oceans,” “lakes,” and “streams.” “Fish finders”—that’s another piece of equipment. “Casting techniques”—now I see that’s its own thing, because there’s probably a whole array of different kinds of casting techniques.

“Kids.” You can take them with you on these destinations, so maybe we’ll have one for “kid-friendly.” Now I can clearly see four different sections, maybe five, because of “casting techniques.” Then I start to create a hierarchy, so I can see: “equipment,” “clothing,” and then stuff to “bring with you” when you go, and a separate section for “fishing-related equipment” that you’ll need before you go out. Already, I can see a chapters and subchapters coming together.

You keep going, and as you keep organizing other chapter topics might emerge. Like, if If I knew a little bit more about fly fishing, I would probably know that there were different flies that I could tie. And that becomes its own chapter to keep filling out. I also know that there are two different kinds of flies, so I’m going to create one for “dry”—those are flies that float—and then “wet.” “Wet” flies—those are the ones that sink. Then within that, I’m going to use a different color to create another level, and put “when to use.” So you can just go deeper and deeper. Then maybe “what to use” based on the type of fish or season.

And you just keep going until you’ve completely exhausted everything you know about your book topic. If you want to watch me going through this process with the fly fishing example, it’s something I cover in this video:

Start the Writing Process

I begin to structure everything, starting at the very top-level. I group things together, and then I start to break things out as it makes sense. This helps me decide what my chapters are, what order everything should be in, what my subchapters are, and my subsections. Then, what I typically do when I start to create this order and start to organize them in a sequential pattern, is start from the top. I pull a group of Post-it Notes and move them over to my computer.

That’s when I start writing about that specific topic. Everything else that’s here over with the Post-It brainstorming project is still there, but I’m not focusing on it, because I’m just writing that one, small section. That’s something I struggle with when writing books. I was envisioning the whole thing, and thinking about every other part of the book and how it was going to relate.

Instead, you’ve got to focus only on that next section. When you do that, it becomes so much more manageable, because as you complete one section at a time and move it aside, then move on to the next, and the next—little by little, you’re chipping away at it. You’re adding more words every single day, and by the end of it, you will have gotten rid of all your Post-it Notes. You start to make progress, and it’s completely motivating.

There’s one more little secret I want to share with you that goes along with this technique, and I’ll talk about that next.

The Technique that Will Dramatically Upgrade Your WPM

You’ve created your Post-it Notes, and you’ve started to see what’s happening in your book in terms of the outline and the chapters, the subchapters, and the subsections within each of those parts. Now it’s time to start writing. Like I said earlier, you’re going to pull out one small section at a time. I might, for example, pull out the sections on how to get involved with “fishing tournaments,” and there’s probably some more hierarchy involved with that topic. I think there are different types of tournaments, so those would go in there as well. Now that you know this is what you’re focusing on—tournaments—you can start writing about it, and your mind is just focused on this topic. Everything else is still there on the table, but you’re only focused on just this one.

Now, for me, writing and actually typing all that out would still be a struggle at this point. Narrowing the topic down into smaller chunks helps me to be a little more focused than I was, but my mind still gets into editing mode whenever I get in front of a computer. It works for blog posts, but when I am writing a book, it just becomes much harder for me mentally. Even though I can try to treat each of these things as a single blog post, I still want to edit along the way, as if I’m crafting it like a blog post that’s going to be published tomorrow.

Now, the very best strategy I know of if you want to upgrade your writing efficiency is to “puke” what’s in your head onto the screen. Basically, you just want to put everything in your brain about your topic onto the page. I know some people who actually take the “delete” button off their keyboard, because they don’t want to let themselves edit, even accidentally. They are just in creative mode. You can edit and move things around later, and you’re probably not going to be using a lot of what you write down, but what comes out when your brain is in creative mode is going to be extremely good for your book.

The problem is that when I’m in editing mode, I’m not letting myself think creatively. I end up stopping myself, because I have to edit this thing and move things around. It’s not what you want to do at this stage. So the big trick I use to overcome this barrier and achieve extremely high word counts per minute is actually an app called Rev. With Rev, I’m not technically writing, as in I’m not typing—I’m dictating my book.

Rev is an app for iPhone and Android. It’s basically an audio recorder, but the cool thing about it is that you can take your audio recording and send it to the people over at Rev, and they will transcribe it for you at $1 per minute. You can even transcribe it yourself or have someone on your team transcribe it for you, but Rev does a really great job. The quality is good, and when it comes back to you a few hours later, it’s all the words you dictated.

So that’s the trick I use to get up to 180 words per minute. It’s how I’ve been able to complete the first brain dump of each of my books. You can’t even really call them drafts, because they’re just everything in my brain about these particular topics, on these Post-it Notes, all dictated. Then I go through the book a second time with a little bit of editing mode in mind, and I can then shape and move things around and craft the stories in a way that makes sense for a book. It’s not going to make sense for a book when it comes from your voice, but you can get so many amazing stories and pieces of your book out through your voice.

So, record it on Rev, transcribe it, and you’ll discover that you have a lot of material to work with. And your book’s going to be finished sooner than you know.

To recap:

- Figure out your WHY for writing a book.

- Determine a topic that you audience wants to learn about from you.

- Brain dump all of your ideas about your book onto Post-it Notes.

- Move them around, organize them, group them, and sequence them to a point where they come to look like a book in terms of chapters, subchapters, sections within those subchapters, and so on.

- Pull out individual pieces and record yourself talking about those each individual item on your Post-it Notes.

- Get the recording transcribed and begin editing.

- If you don’t want to go the audio recording route, that’s fine; you can write about the topics instead. But having that single Post-it note there to keep you focused is going to help quite a bit.

We’ve covered a lot in this first chapter. So what do you do once you have a draft? Next up, we’ll look at editing your book so that it’s closer to publish-ready.

How to Edit Your Book Before Publishing

Once you have a complete manuscript draft, congratulations are in order. It’s a big deal to finish the draft of a book project of any length and that is definitely cause for celebration. But! Don’t rest on the laurels of that accomplishment for too long, because finishing the manuscript is only the first step. As much as we hate to break it to you, we must be the bearer of the reality check that your work has only just begun.

Your next big step will be to hire and work with an editor to get the book publish-ready.

It’s all too common in the new world of publishing for writers, especially online content creators, to have one of two misconceptions about the editing process. They either 1) assume that their work is good enough as it is and doesn’t need editing, or 2) don’t fully understand what working with an experienced professional editor can do for their work. If your perspective on the editing process is some combination of these two misconceptions, read on.

That’s what this chapter is all about: helping you to understand the editing process, what working with an editor is like, and what an editor can really do for you. The first thing we’ll say is that all writers need editors. It doesn’t matter who they are or how good they are—the best and most popular writers all have editors. Editors are the first line of defense for writers. They are your earliest official reader, and they help you to ensure that your work is ready for a larger, more public audience.

Think of it this way: Every year the president of the United States gives the State of the Union address, and that speech is written and revised and critiqued and revised and rewritten some more before it’s in the final form that gets delivered to Congress. Now, granted, your book is probably not as seminal a work as the State of the Union (not yet anyway!), but the point is that if the president of the United States takes that much care in crafting his message, then don’t you think it’s a valuable component when communicating something that is important to you?

Communication is often tricky, especially when you are attempting to introduce readers to new or unfamiliar ideas, because you have to ensure that you lead your reader on a logical path so that they can follow along in your thinking. That means that the sequence of how you present information is incredibly important. The breakdown happens when the complex idea that you are attempting to communicate on the page appears clear to you because it makes sense in your head, but it may not make sense to an objective reader. Your reader is not a mind reader and not intimately involved with your logic or thinking—you are the only person who knows what’s going on inside your head—and that’s where an editor comes in. The editor helps you to sort out and organize your ideas so that they are clear to anyone who encounters them, and so that they do make sense to readers who are new to the concept.

You may recall that a lot of us here at Team SPI have background and experience as editors. In that experience working with authors we have encountered writers periodically who, when we gave them feedback, attempted to verbally explain what they meant. This is usually an indication that the author didn’t communicate clearly and didn’t sufficiently translate what was in their head onto the page. The problem is if it’s not on the page, readers will not have access to you, the author, to get clarification on a topic or a point when they are reading your book—all they’ll have is the book, which means you need to make sure it’s as solid as it can be to stand on its own and communicate effectively on your behalf.

Everyone says my book is great; why do I need an editor?

You may have already had friends and family read early drafts of your manuscript, and you may have already revised to incorporate their feedback. That’s a great strategy to get your draft ready for an editor. And, yes, unless your significant other or best friend is a professional editor, we do still advocate hiring a professional even after you’ve passed your manuscript around to your personal network. (For the record, Pat has worked with professional editors for all of his self-published books. He shares more about that experience for his book Will It Fly? In chapter 3.)

As much as your friends and family love you and want to support you, unless they have training, there are things that only a professional editor will be able to do for you. First and foremost a professional whom you pay to work on your manuscript is going to give you critical, strategic, and objective feedback that people who know you are likely not in a position to give. When you hire an editor, you’re entering a business service relationship, in which the editor has a professional responsibility to help you create the best book possible because your editor will be invested in delivering the best work possible to you, the client.

Objective feedback is essential. You parents or your spouse or your best friend or whoever you’ve asked to read your early draft are probably more concerned about whether or not they hurt your feelings than they are with giving you feedback that you can actually apply toward improving your book. Not so with an editor. Beyond objectivity, your editor will also provide you with critical and strategic feedback. By critical feedback, we mean that your editor will analyze your draft and identify its structure and order, making suggestions to rearrange material if necessary. Your editor will also identify material that might get off track and make suggestions of where to cut, and where to expand if the material is lacking and needs further development.

Editors also think critically about your target audience, which may be something you haven’t given much thought in your writing process. That’s okay because 1) when you’re writing you need to just get the material on the page, and 2) that’s part of the revision process that an editor can help you with. This is the stage where you refine the manuscript to include references and examples that are relevant to your audience, and maybe take out the obscure Back to the Future reference unless, of course you are Pat Flynn, and you know your niche audience will get it.

More than anything else, hiring an editor means bringing on a teammate. With an editor you’re no longer a team of one, you’re a team of two. Your editor becomes your coach, your cheerleader, and your partner. If you find a good editor, someone who understands you and your book and who works well with you, then that person will be just as invested in the book as you are—and that’s what you want. You want someone who cares about your message as you do so that together you can produce the best possible manuscript. We’ll talk more about how you find that person, but first let’s talk about the different types of editing.

How do I know what kind of editing I need?

You may not know what kind of editing you need without first consulting an editor. That may seem a bit counterintuitive if you’re wondering how you hire someone if you don’t even know what type of service to look for. Don’t worry—most editors and content service providers will offer an entry-level service such as a manuscript evaluation, which would help you to identify the type of editing you might need.

Here at SPI we take our books through three levels of editing and define them as follows:

- Developmental editing is all about structure, flow, and story design.

- Line editing focuses on your manuscript line by line to improve language, word choice, tone, sentence structure, etc.

- Copyediting concentrates on bullet-proofing your manuscript, looking to correct errors in the areas of grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc.

Typically the first and best place to start is with a round of developmental editing. Unless you’re an experienced writer with more than one book under your belt, chances are that you’ll need to do some restructuring, reordering, and rewriting on the manuscript before it’s ready for the next stage. This is where you get the structure and order, what’s often called the narrative arc of the book, finalized. If the draft is super rough, then this phase is all about simply determining the focus of the book, eliminating anything that doesn’t support that focus, and identifying what new material needs to still be written to make the focus work. You don’t want to do a lot of the nit-picky corrections that happen in the copyediting stage before getting the structure nailed down, because you’re often writing new material, moving material around, and introducing all kinds of new errors in the process.

Once you are done with developmental editing, you can move on to line editing and copyediting, which is beginning to fine tune and polish up the manuscript. Whereas developmental editing works at a higher, holistic level, line editing works at the lower, sentence level. This phase of editing ensures that sentences flow from one to the next, that there are appropriate transitions between sections, that there’s a solid finish to each chapter, and that your word choice throughout is consistent with the tone you’re using to speak to your audience—for example, line editing would eliminate the introduction of profanity mid-way through your manuscript, because it would be jarring to readers if it is not part of the tone you’ve set with them from the outset.

In addition to correcting grammar errors, copyediting also ensures that your manuscript is consistent throughout with style choices like, for example, whether to use SmartPassiveIncome.com vs. Smart Passive Income vs. SPI. Copyediting is often combined with a final round of proofreading to catch any straggling errors, but in traditional publishing houses you’ll find that copyediting and proofreading are two separate roles and proofreading is the last step after a manuscript is laid out and before it goes to press. Every manuscript needs a minimum of copyediting and proofreading. Whether you also need line editing depends on how messy your manuscript is to begin with.

What is it like to work with an editor?

A good editor is like a business partner: You both have defined roles and responsibilities on the project and you both are working toward the same goal of making the best possible book. Your editor will challenge you and probably give you feedback that you don’t like or is a little uncomfortable to hear at times. But it’s all with the intention of bringing out the best writer in you. Your editor will also be your biggest cheerleader, identifying the strengths of your work often by asking for more of the same. And, if you think you will write more than one book, you may find that you continue working with the same editor for years because you’ve built a relationship with someone who not only knows your work but knows how you work.

One of the most important things to know about developmental editing is that it does not mean that the editor is doing the work of rearranging and rewriting. A standard deliverable for a developmental edit is a written critique, evaluating the following elements of the manuscript and making recommendations for each:

- structure

- opening/introduction

- conflict

- setting/context

- show vs. tell

- language

- point of view

- ending/conclusion

- formatting

- grammar/spelling

A developmental critique means you end up with a list of homework assignments from your editor and you go to work revising based on the editor’s recommendations. The editor is often available by email or phone to answer questions as you work on the revisions and then to review your manuscript one more time when you have a revised draft ready. You can expect more back-and-forth and a longer-term relationship with developmental editors, who are spending more time with you and with the manuscript, helping to inform the shape of the book and helping you to make decisions. There are even some developmental editors who will sub-contract for line and copyediting, and in that case you may not have contact with the next level editors.

With line and copyediting, you can expect an editor to make corrections directly in the document. The deliverable at this stage typically includes two files: one marked up file with the changes tracked, and one clean file with all changes accepted. Copyeditors will likely ask for a style guide that dictates treatment of words and punctuation specifically for your book. If you don’t have one, then they can also help you create one; it’s usually one page or less listing book-specific style choices that supplements the designated style guide you’re following such as The Chicago Manual of Style or The Associated Press Style Guide.

Keep in mind that editors often prefer and specialize in one type of editing. Developmental editors in particular may even specify that they will not copyedit a manuscript after they’ve done the developmental edit, and vice versa. Line editors almost never also copyedit. And copyeditors never proofread. The reason is that once you get to the next level of editing, you want a set of fresh eyes on the manuscript. The more familiar you are with the work, the more likely you are to miss something. Not to worry, most editors have a network of professionals in the field and can refer you to someone for any type of editing that they don’t do themselves.

How long will editing my book take?

That’s a hard question to answer because it depends so much on each individual book manuscript and, really, the author. There are so many variables, like how long the manuscript is, how much development it needs, how strong of a writer you are, how quickly you write, and, perhaps most importantly, how dedicated you are to the revision process.

The short answer to the question is, it depends on you and how much time you give it. If you get a developmental critique and you’re able to implement the recommendations within a week or two, you’re that much closer to having a finished manuscript. But if you are able to dedicate only a few hours on the weekends, it could take you several weeks or months to finish. So, bottom line is, it’s largely up to you how long it will take.

How do I find an editor?

Finding a good editor who you click with and want to work with long-term can be a bit tricky. It’s not like looking at a beautiful website, knowing you love it so much that you want to work with whoever designed it. The work of a good editor is hidden behind the scenes and unnoticeable—and that’s the point. An editor’s job is to make the author look good. When you love a book you think it’s well written, not well edited. So if you can’t see the editor’s work, how do you even know where to start?

Of course there’s always the good ol’ Google search, although you never quite know what you’re going to get there. Some of the trusted resources for authors online include sites like Jane Friedman and Joanna Penn’s blogs, where you’ll find resources listed for help with your book including editors. But in our opinion, the best way to find an editor is word of mouth. Ask your author friends who they have worked with in the past, and what their experience was like. If you don’t know anyone who has written a book and worked with an editor, there are professional organizations that provide directories for their members and some, like the Editorial Freelancers Association, have a job board where you can post a listing for your project and request proposals or quotes from interested members. You could also use a site like Upwork to find a freelancer for any type of project, including editing.

My book has been edited, now what?

You’re on your way! And you still have a lot of work ahead of you, including some important decisions about how you want to proceed. Do you intend to self-publish, or try to get a traditional book deal? Keep reading; we’ve got a chapter to give you an idea of what to expect from each avenue that will help you to make an informed decision. But first we need to cover how to get your manuscript ready for publishing, and we’ll get to that in chapter 3.

Get your free Book Publishing Cheat Sheet.

Learn the step-by-step publishing process guidance and get a high-level overview of the 5 stages of publishing. Our cheat cheat sheet covers steps for both ebook and print.

How to Get Your Book Manuscript Ready for Publishing

Deciding to write a book means a long term commitment to get it written, published, and ready for distribution. It’s not an overnight thing by any means, and it will test your limits. It did for me, but seriously, it feels really good once it all comes together.

This chapter is super-detailed sharing everything that involved in getting my book Will It Fly? ready for liftoff. We’ll cover a wide range of topics, from how I validated the idea for the book and how I wrote it, to how I found people to help edit it and how it was finally released into the wild with the goal of producing optimal results. In other words, all of the behind-the-scenes stuff that went into getting the book ready to publish.

I’m going into so much detail because I hope this will help you plan your own book, course, or product launch. Will It Fly? was written to help you get started building the business of your dreams, and I want this guide to be one more tool to help you get that business off the ground.

Getting the Book Ready to Publish

Writing Will It Fly? was a major challenge for me. Quite honestly, it was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. I could have had the book ghostwritten, and I did have several offers to ghostwrite the book, but I chose to do it on my own. I really wanted to write the book on my own for personal reasons—so that I could be truthful when I say I wrote this book—but I also because I wanted others to see my example struggling through the process, conquering the fear, and putting in the hours in to get it done.

Now that it’s out there and in people’s hands, it feels good knowing I did it all on my own. That’s not to say I didn’t have help with content development and copyeditors, which we’ll get to later in this chapter, but to have put fingers to keyboard on my own book feels really good.

That’s not to say, however, that hiring a ghostwriter is bad. In many cases, it’s the right decision, but for me and for this book, I needed to do it on my own. Here’s an overview of the process for getting this book ready to publish. I’ve broken it down into these six stages:

- Stage 1: Outlining and Writing a Quick First Draft

- Stage 2: Revising a First Draft into a Second Draft

- Stage 3: Another Pass at the Second Draft (This Time with a Different Tool)

- Stage 4: Working with a Developmental Editor

- Stage 5: Designing the Book Cover & Interior

- Stage 6: Uploading the Book for Pre-Orders Through Amazon with CreateSpace

Stage 1: Outlining and Writing a Quick First Draft

The purpose of a first draft is to brainstorm. Shannon Hale, an award-winning author who has written more than twenty books, said it best: “I’m writing a first draft and reminding myself that I’m simply shoveling sand into a box so that later I can build castles.”

The trick is finding the best method for shoveling all that sand. For me, it was the method I shared in Episode 1 of SPI TV and in detail in chapter 1 of this guide:

After only two weeks, my first draft ended up totaling more than sixty-five thousand words, but ended up keeping less than 10 percent of that first draft moving forward. That 10 percent, however, was key. In the end, I hardly used any of the exact text that I dictated (and then transcribed) in the final manuscript, but that brainstorming session was definitely necessary for me to think about ideas and come up with material that wouldn’t have come out otherwise.

Stage 2: Revising a First Draft into a Second Draft

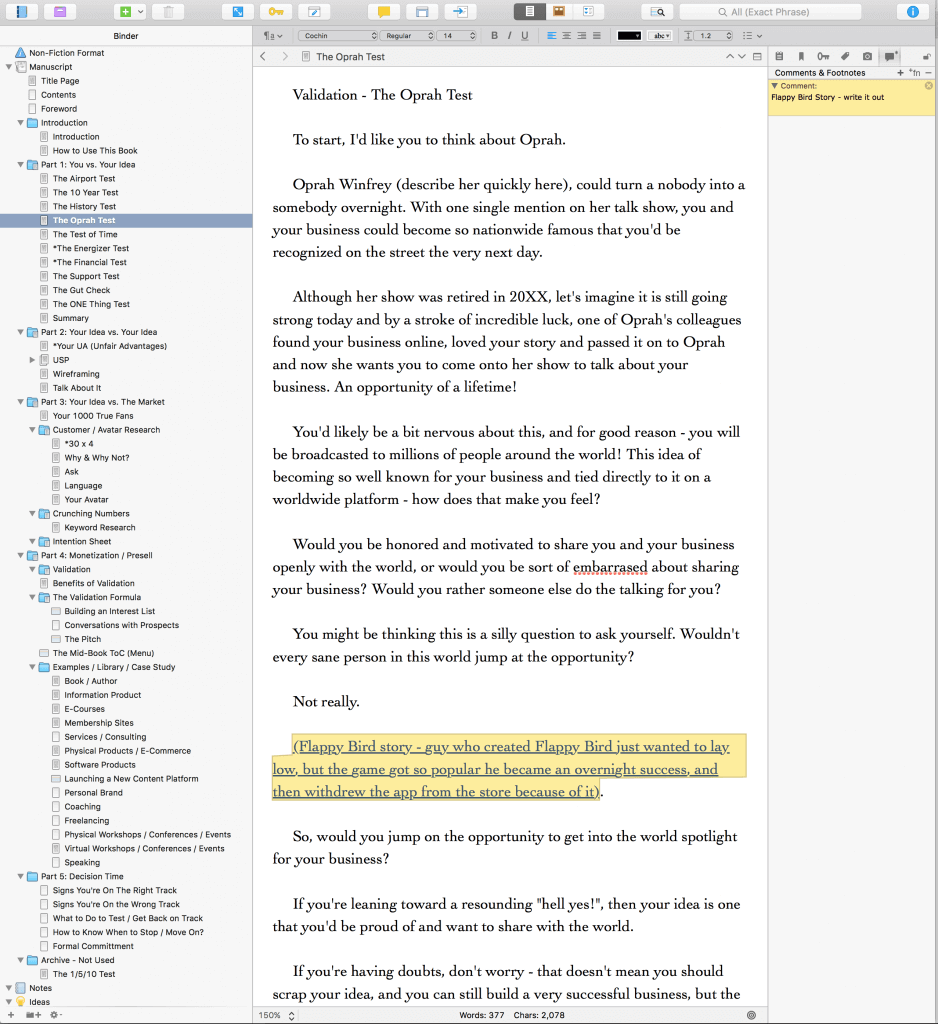

The next phase was to take what I had dictated and transcribed in my first draft, pull out all of the best parts, and then transform all of that into something cohesive that I could dive much deeper into. This started with creating a detailed outline of the book to nail down all of the parts that I wanted to include. You can see the start of what this looked like here on the left hand column:

This is a screenshot of a tool for authors called Scrivener, and it’s the one that many authors of both fiction and nonfiction use to write their books. I used it to write my first book, Let Go, so I figured it would be easy to pick up again.

It was not.

Let Go was a much shorter book with a smaller and less intimidating outline. When I entered the outline for Will It Fly? here (which, by the way, was not titled Will It Fly? yet—it was simply called Validation Book as a placeholder) it became super intimidating and as I began to get into the chapters of the manuscript, I started to see just how long this journey would take.

I actually stopped writing for about two months at this point, because it was hard. I made excuses and although I did put writing into my to-do list for the day, I’d always prioritize something above it, and so it never got worked on.

It wasn’t until May of 2015 when I made the decision to get the manuscript done by the end of the year that I got serious and hired a coach, Azul Terronez, to help me through the process.

Getting a Coach

I needed help.

I don’t say that like I was in trouble, but I say that meaning that whenever I finally make the decision to really go for something, I need the help. I need help because I know there are people out there who are better than I am at certain things, who I can learn from to get better results. So when it came to writing this book and knowing I was letting myself down, I found a coach for authors who I knew would be able to help me through the process and hold me accountable.

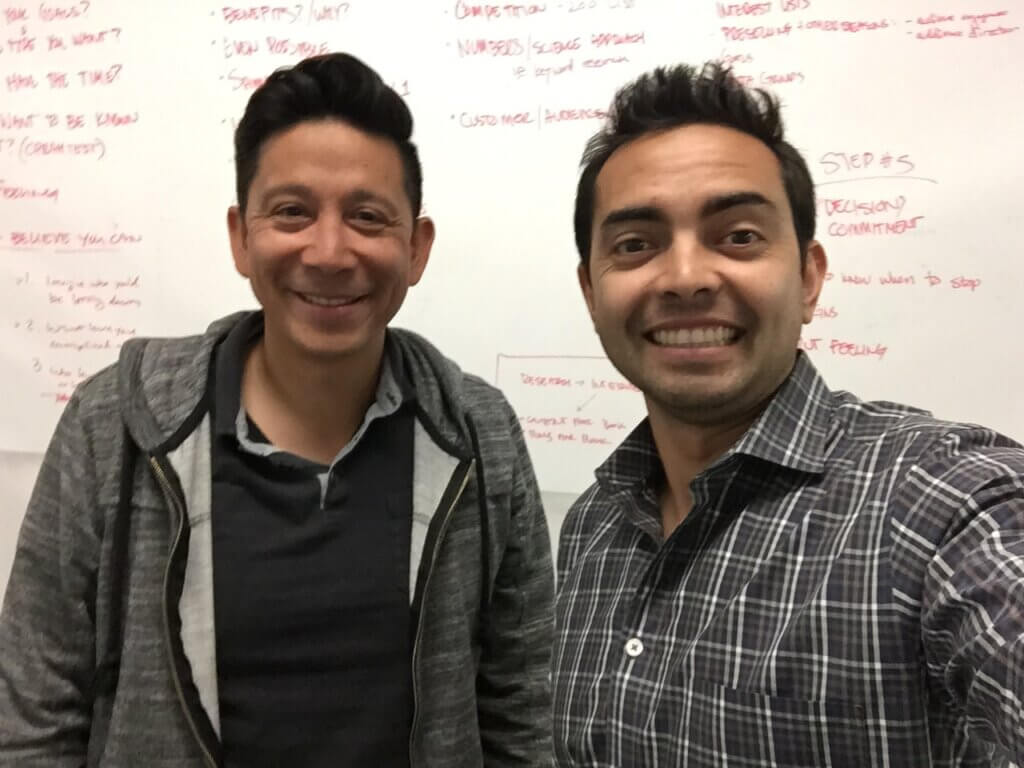

Azul was actually a student at one of Chris Ducker’s and my 1-Day Business Breakthrough Live Events. After keeping in close contact with him, when he learned that writing this book was a big goal of mine, he offered to help, and I gladly accepted. Since he was in San Diego at the time, we met in person to discuss and brainstorm next steps.

He was quick to address the mental roadblocks that I was facing, and he gave me specific deadlines for finishing certain parts of the book, which was helpful. That added pressure was key for me to get the motivation to sit down to write each day.

Here’s a photo from one of our sessions together at a coworking space in downtown San Diego:

Two other things Azul was super helpful with:

First, it was with encouragement. I told him that I work best when I know someone is rooting for me on the other end, so he would send me texts and emails randomly every so often rooting me on while I work toward the next deadline.

Second, he helped me realize just how much each section of the book was like a blog post. I knew this in the back of my mind, but his instruction to intentionally treat them as such helped out tremendously. Instead of writing in Scrivener, which is what I thought I was supposed to do, he suggested that instead I write the book using whatever tool I used to write my blog posts, which happened to be Google Docs.

Stage 3: Another Pass at the Second Draft (This Time Using a Different Tool)

When I shifted to a different writing platform, everything flowed so much easier.

Why?

Because it was a comfortable, non-intimidating environment I was used to! Writing in Google Docs took away the overwhelming outline that I could always see in Scrivener, and it kept my focus on the chapter I was working on, and that chapter only.

By the time August came around that year and I was back from vacation with my family, I was in full writing mode, and the book was going to be my ONE Thing (a concept I learned from the book The One Thing by Gary Keller and Jay Papasan) until it was complete. [Full Disclosure: As an affiliate, I receive compensation if you purchase through this link.]

I got into the habit of writing every morning between 6 and 7:30 a.m., because it was the only time I could fit it in. As soon as my kids woke up, my writing time was over for the day unless I could squeeze in any more uninterrupted time, which was unlikely. Soon enough, the parts of the book started to fill out, and I was excited to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

A Note About Structure

A good nonfiction book needs structure. Without it, you’ll end up with a mess of a manuscript that needs untangling before it’s ready for your readers. You might be tempted to rush through the outline stage, but let me tell you: don’t do it! It’s super helpful to get your chapters organized and ordered, because then you can approach writing and revising your book in chunks.

Beyond chapters, there are other elements of a book structure to help you organize and present your material in a logical organization that helps readers navigate the book. Think of the structure as a map for the book, and it eventually gets turned into the table of contents. The structure can also include

- Parts: a collection of chapters organized around a theme or timeline

- Chapters: main segments and building blocks of any book

- Subchapters or sections: smaller segments that organize ideas or topics inside chapters

Once you have your chapters you then have to figure out the best way to order them. For nonfiction books sometimes a chronological time-based ordering makes sense but I think mostly commonly you’ll see a step-by-step order leading the reader through a sequence of steps designed to help them achieve a specific outcome.

The step-by-step structure is what I did with Will It Fly?, because it’s all about helping people validate their business idea, and I ended up with nineteen chapters segmented into five parts (not including front and back matter, which we’ll get to later in this chapter). It’s a structure that developed throughout the editing and revision process.

Deadlines—EEK!

Azul’s deadlines were extremely helpful for keeping me on track, but as soon as I saw that the end of the first pass of the manuscript was in sight, I realized just how much more work beyond the manuscript itself was needed, and therefore how much more I had to think about, especially related to the timing of everything.

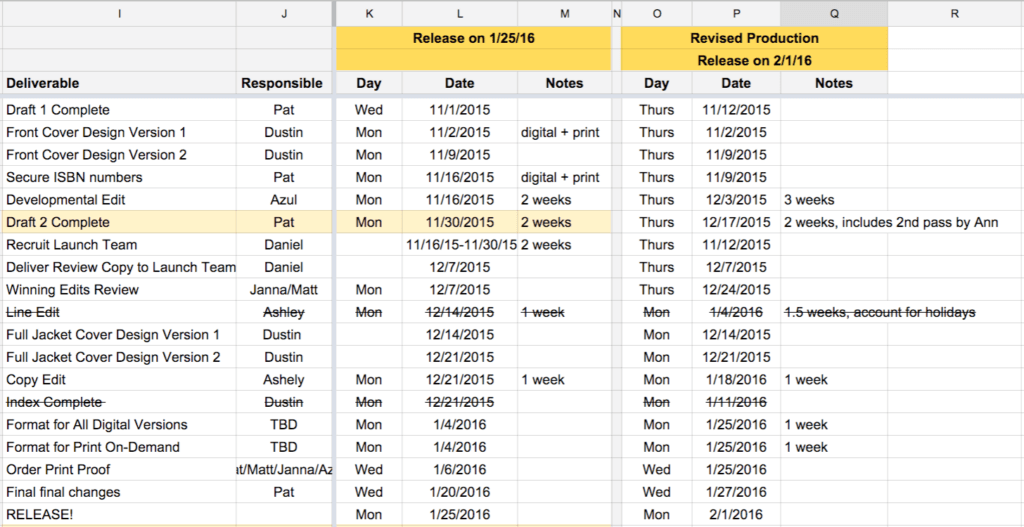

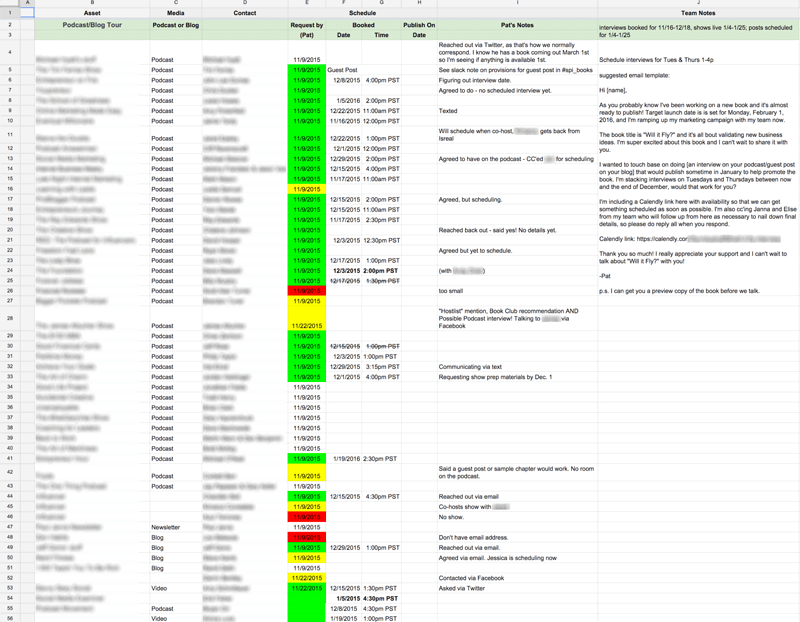

Team SPI (Matt and Janna, primarily) and I worked together on creating various schedules based on when I might be able to get the book done. Here’s what those look like. They work backwards from various publication dates, and include all of the timelines for all of the other things involved:

As you can see, we were exploring a 1/25/16 launch date initially, but we decided to have it come out a week later to give us an additional week for production purposes, which we later found out was completely necessary.

My biggest concern was having the manuscript finished in time to give the developmental editor, Ann Maynard from CommandZContent.com, so that she had enough time to review it and get it back to me before Thanksgiving break.

The deadline was November 1, but it got pushed back to November 12 because I got sick and was unable to get it done in time. This made me nervous, because we were supposed to launch on February 1, less than three months away at that point. The clock was ticking, and we still had copyediting to do too! Luckily, I had Azul and Ann in my corner. Here’s a good example of one of those encouraging emails:

Stage 4: Working with a Developmental Editor

Spelling and grammar are important, and it’s one of those things that no matter how much you try yourself, you’re going to need separate sets of eyes to catch those last minute mistakes.

However, even before working with a copyeditor, there’s the developmental editor, which isn’t so much about spelling and grammar, but rather the flow, order, and structure of the content within the book.

Before working on this book I didn’t know developmental editors existed, and I found out just how great it was to work with one. A few weeks after handing my first manuscript over to my developmental editor, Ann, I received some invaluable feedback. I didn’t have to rewrite the entire manuscript (thankfully!), but I did add some additional components and re-order a few things that took the book to higher levels.

I recorded a conversation that I had with Ann and Azul after getting back the first round of editorial notes. This is a very in-depth conversation, and I did receive permission from Ann to share this with you. This isn’t available on the podcast, only here as a bonus for those of you who care to listen.

It’s over one hour long (at normal speed), but it gets into a lot of what was wrong with the first pass, and what I could do to make the second pass even better:

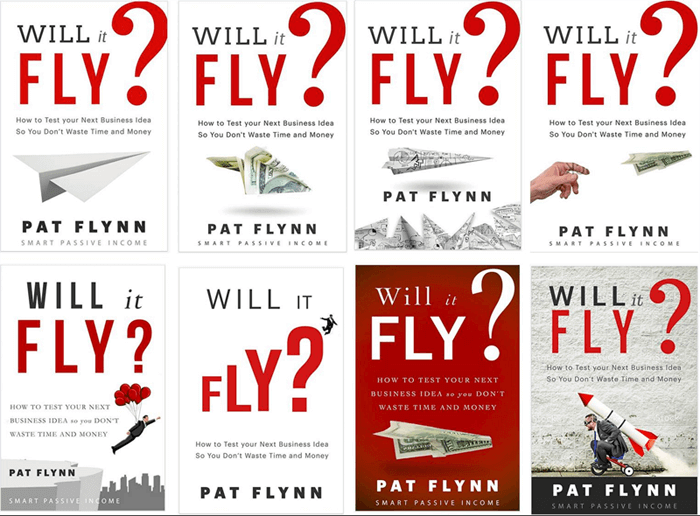

The most encouraging note, however, came from Ann via Azul over email. After she read it over the first time, this is what she said:

![The email from Azul reads:

"Hey Pat, I have been in communication with Ann, she has some questions about some content that I need to make sure she has so she can pass off the first polish to us. I am working on that now.

"Here's a note from here [sic] to you:

"'It's a rare thing for me to mutter, 'clever,' as I'm reading the closing sentences of a first-pass manuscript. Yet, that's exactly what I did with Will It Fly. (My dog heard me and thought it sounded close enough to 'breakfast' that it warranted begging around his food bowl, haha.) There's great content here. It's engaging and accessible without sacrificing actual value. None of the exercises included in your manuscript feel tacked on, and each one's purpose is very intuitive. And that's a VERY good (and surprisingly uncommon) thing. Even better, there are a few opportunities that have been laid at our feet to take the existing text even further. I'm very excited to talk through next steps!'

"I will shoot you a text soon once I get her what she needs.

"So exciting Pat"](https://www.smartpassiveincome.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Email-from-Azul-and-developmental-editor-Ann-1024x841.png)

Wow, I mean—I couldn’t have felt any better after reading that! I knew there would be changes, and because I was so amped (and under a ton of pressure with the upcoming deadline), I was ready to make changes and submit to Ann a second go-around. I was able to knock that out in just two days. That’s unusually fast for a revision, however I spent every waking hour during those two days making it happen. Furthermore, how long it takes you to turn around a revision depends on the number of edits to make within that manuscript and a whole number of other factors. Luckily for me, the direction was clear, I just needed the time to do it, and I took all the time I had.

After the manuscript had Ann’s blessing, it was then ready to be passed on to the copyeditor, which was someone on my own team who has experience with copyediting various content for me.

And finally, if you get a chance, even though you might hire an editor of your own, make sure you spend some time reading through your manuscript . . . out loud. Hearing yourself say the words in your book will help you find even more mistakes that often get skipped over when just reading the text in our heads. (Be sure to revisit chapter 2 for more on editing and working with an editor.)

Let’s Not Forget the Front and Back Matter

What are the front and back matter parts of a book? Well, a book—a real, actual published book—is more than just the words you write from Chapter 1 to Chapter Done. There are a few more pieces that need to come together before your book is fully fledged and ready to fly off shelves.

These elements are known as a book’s front and back matter, the smaller sections that appear at the beginning and end of a book. They help set the stage and context about the book for your reader, provide them with additional information and resources if they want to learn more, and help them stay connected to you as an author. Here’s a quick rundown of these other pages you might forget about, but are a part of the book’s structure:

Front Matter:

- Copyright page: includes copyright information, ISBN, edition notice, date of publication, number of printings, disclaimers, warranties, and safety notices, publisher’s address.

- Full title page: includes the full title, subtitle, author’s name, publisher’s name and city.

- Half title page: includes only the title of the book, usually immediately following the full title page

- Praise: A collection of quotes and endorsements from advance readers.

- Table of contents: An ordered listing of the contents of the book that details the chapters and (possibly) subchapters.

- Dedication: A short section written by the author that mentions the person or people for whom the book was written.

- Epigraph: A quote that may be inspired by but not directly related to the topic of the book.

- Foreword: A brief essay written by someone other than the author but who is well-acquainted with the author or the book.

- Preface: The author’s introduction to the book as a book, with an explanation of why and how they wrote the book.

- Introduction: The author’s introduction to the content of the book, which lays out the purpose and goals of the book as well as sets up the first chapter.

- Prologue: The opening of the book, used to explain important information that doesn’t follow the chronological flow of the rest of the book.

Back Matter:

- Appendix (or Appendices): A supplement to the book that usually includes referenced documents cited in the text, or books and resources on related topics that may be of interest to your reader.

- Glossary: An alphabetical list of terms and concepts found in the book, with explanations.

- Index: An alphabetical list of terms and concepts found in the book that allows a reader to locate mentions of those terms in the book.

- Bibliography: This is where you add citations for all the reference materials used in your research: other books, websites, journals, etc.

- Afterword: The afterword can be an alternative to a preface. It can also be written by someone else. In updated editions of books, the author may include an afterword reflecting on the reception of the previous edition and what he or she has learned since then.

- Acknowledgments: The author’s thank-yous to people and organizations that assisted in the writing of the book.

- About the Author: A brief biography of the author.

- Other bonus material we’ll talk about in a minute.

For Will It Fly? I included the following front matter:

- Title Page

- Praise Page

- Copyright Page

- Course Promo Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

And back matter:

- Resource Page

- Let Go Page (promoting my other book)

- Acknowledgements

- About Smart Passive Income

- About the Author

And that’s the thing, when you’re self-publishing your book, you have the freedom to include anything you want in the front and back parts of the book. Don’t let these pages fool you, although they are just one to a few pages in length, they do take some time to complete, and your manuscript will not be ready for interior design until they’re complete.

Back to the Deadline Real Quick

At this point, you might be wondering why we were still going through edits so close to the launch of the book.

To be honest, it was a combination of a lot of things:

- Being over ambitious with the timeline.

- Not giving ourselves a ton of flexibility and lead-time, especially when it came to developmental and copyediting.

- Me getting sick.

- The holidays, and wanting to respect people’s time with family.

To launch a book in February means a ton of work needs to be done around November and December, and with Thanksgiving and Christmas, it takes away a lot of the time you might think you have to get everything done. (We talk more about this in chapter 10 on publishing mistakes.)

The plus side, however, is that because most people tend to slow down during these months, if you can speed things up you’ll have a slight advantage. This was definitely something I felt because when the book launched, it wasn’t up against anything else in launching the same category. Most other books, at least in the business category, seemed to come out in early January, or were scheduled to come out in March. It was the perfect window for Will It Fly?, and so I was excited to see what the results were, which are coming later in this guide.

But back to production stuff, because there’s a lot more to a book than just the manuscript. There’s the design of the book, too, both the outside and the inside.

Stage 5: Designing the Book Cover & Interior

The cover of a book is extremely important, especially if you’re going to be publishing it on Amazon. (More about how to think about the design for your book coming in chapter 4.)

The cover is the first impression people have of your book, even before they read it. A good cover helps your book to either stand out or blend in, and it can set the tone of the content for your reader.

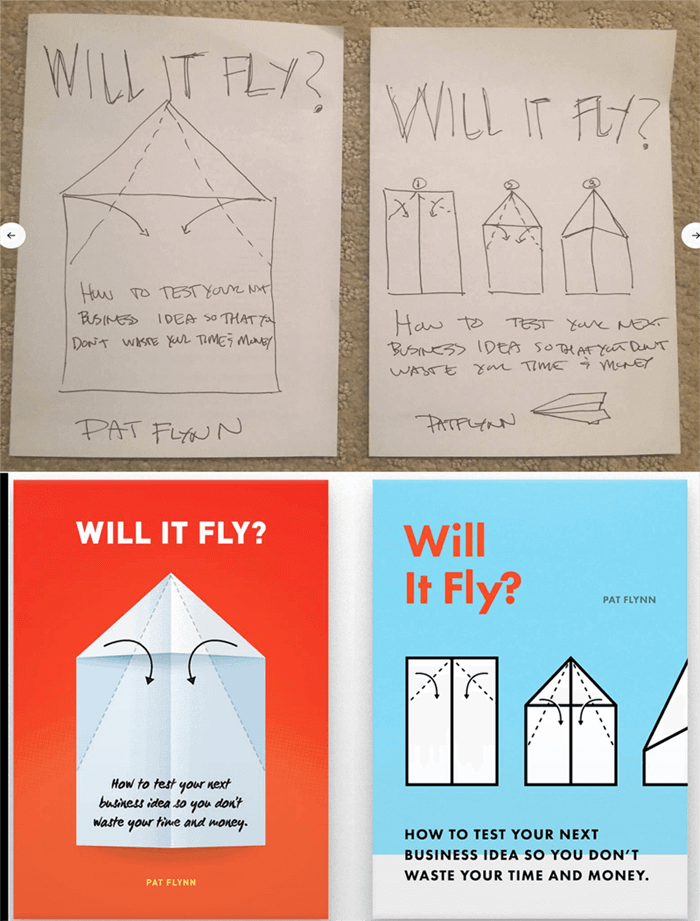

Will It Fly? opens with a story of my son and his first experience folding a paper airplane (spoiler: it doesn’t go so well), and so I thought a paper airplane on the cover would make a nice visual for the cover. Plus, paper is what we write ideas on sometimes, and the purpose of the book is to see if those ideas can fly.

So, I drew a little sketch and had Dustin on my team come up with some early concepts:

At first, I was happy with what I saw, but after the initial excitement died down, I knew that there could be room for improvement, and I wanted to see more iterations before making a final decision. I had also expressed the idea of sharing a single image of a folded paper airplane beneath the title, and so here was the next batch of design concepts from Dustin:

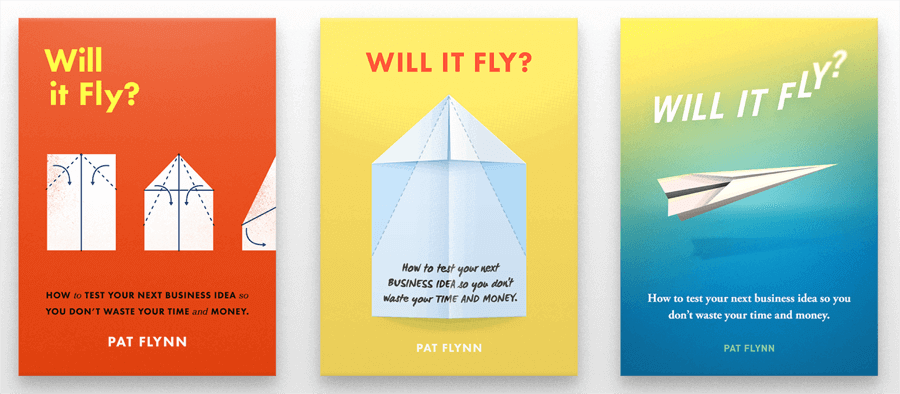

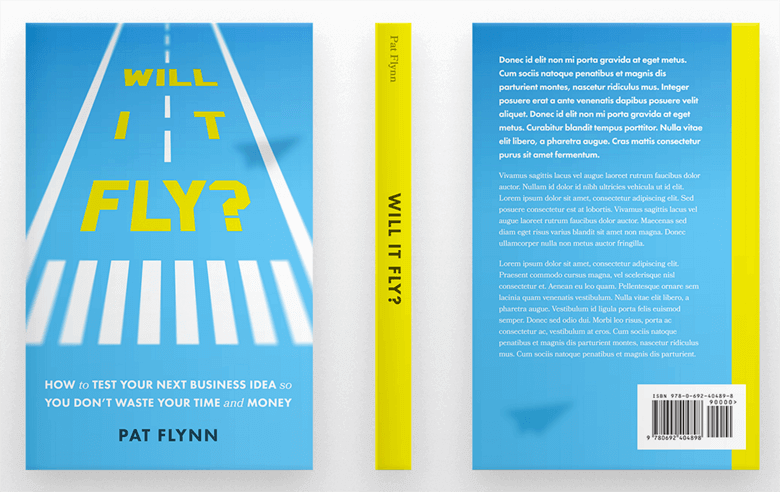

We were getting there, but I had yet to feel that “hell yeah” that I wanted when looking at the cover. I started to share these concepts on social media and with the book’s launch group to get a first reaction, and it was mixed. Also, a number of people found books with similar covers on Amazon, including this one, that was great:

After about two weeks and still struggling to find a design that worked, Azul and I ended up reaching out to another designer to see what it would look like coming from another person’s perspective. Having read only the introduction, another designer came up with the following iterations:

There were parts of this I liked, for example the font treatment, which made the title stand out much more, but the images seemed a little too stock for my liking. Plus, then another member of the launch group found this image from Jeff Goins’ book The Art of Work:

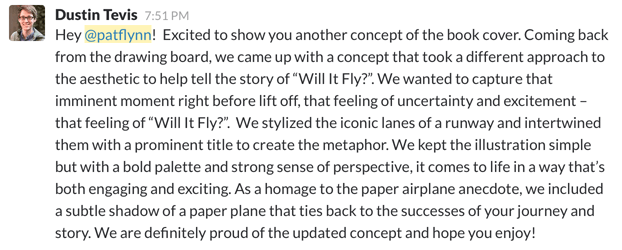

This was all happening while I was finishing up the manuscript, and after sharing with the team that I wasn’t happy with any of the submissions yet, Dustin took one final crack at it from a totally different viewpoint, and here’s what he came up with:

This was the “hell yeah” I was looking for! It still needed a couple of tweaks though (the spacing of the word “it” was really bothersome), but after playing around with it a little and darkening the blue to make the title stand out, we had our final version.

Photoshopping various thumbnails into Amazon at the smallest size:

The final front cover design before going live:

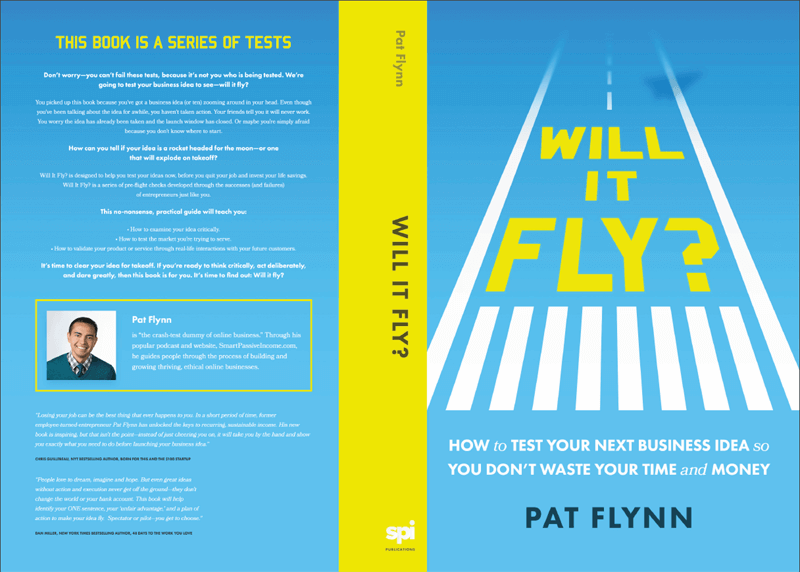

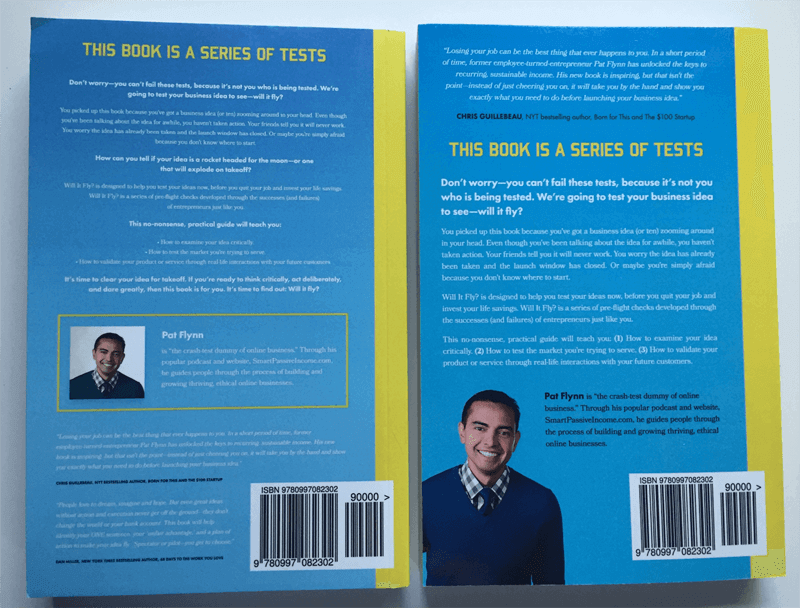

Since this was a paperback book, the back cover and the spine also had to be designed. To help us with the right specifications, since this book was being printed through Amazon’s print-on-demand service, CreateSpace (now part of Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing), Dustin referenced this document here.

The interesting thing is that he couldn’t determine the size of the spine until the book interior design was complete, because it’s the interior design that determined how many pages the book would to be, and obviously the more pages there are, the thicker the spine.

The back cover was a lot of fun to play around with, because it’s where you can add any blurbs and copy about the book that you want, and we also decided to add in a picture of me.

Unfortunately, what you see in a PDF file isn’t always what you get in your hands once it’s printed. Again, likely due to time constraints, we realized after going live that the back cover font was far too small. We immediately updated it to get it to the right size, but a handful of initial buyers have what I like to call the super rare early edition misprint.

Here’s a before (left) and after (right) comparison:

I’m very happy with how it turned out in the end, and coming from a print-on-demand service I was a little skeptical at what the quality would look like, but I was pleasantly surprised when I received my first copies in the mail:

Designing the Book Interior

The interior design of a book is just as important as the text itself, because a poor design or layout can make even the best of content hard to digest and tough on the eyes.

For a print book, interior design includes everything that you see when you flip through the pages: spacing, font size, drop caps, page numbers, headers, page breaks, chapter titles, images, bullet points, callouts, and featured sections.

For a Kindle ebook, it’s all of that, plus clickable links, and making sure the file is compatible to various device types and sizes.

This part of the process, by far, is one where I wouldn’t even know where to start if I had to do it on my own, so with the help of Azul, I found two people to help convert the manuscript into the final files that I would be uploading for approval and distribution.

Each format design took about a week to get the job done, and that is a quick turnaround. We were lucky to find people available to work fast on our deadline to meet our launch date, but usually these professionals need anywhere between two to four weeks to complete book design, layout, and corrections. Although the design was an upfront cost, I knew this was an extremely important part of the process and I didn’t want to skimp on it, but (as with editors), you may be able to find great work on sites like Upwork as well.

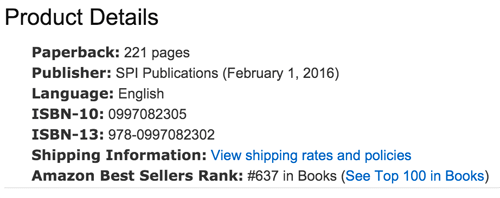

ISBN

Before getting your book up for sale on any platform that’s not your own site, you’re going to need an International Standard Book Number (ISBN), which is a thirteen-digit identifier for your particular book. The ISBN is used within the publishing industry to keep track and facilitate activities related to your work, like sales and distribution.

If you’re publishing on Kindle, you do not need an ISBN. Amazon will hook you up with a unique Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN) if you’re publishing through Kindle Direct Publishing.

If you’re publishing a print-book, you’ll need an ISBN. To get your ISBN, head on over to www.MyIdentifiers.com, where you can purchase your ISBN and barcode from Bowker’s Identifier Services.

Information About Your Book

When you register each version of your book, you’ll need to enter a few pieces of information that are always good to have on hand. You’ll need these anyway when you enter information into Amazon and any other platform where you choose to sell your book, so let’s define what they are. Here’s what you’ll need:

- Title

- Subtitle

- Description

- Author / Contributors

You’ll also need this info when you create your book listing on Amazon or any distribution platform. So let’s look at that next: getting Will It Fly? listed, officially published, and ready to sell!

Stage 6: Uploading the Book Pre-Orders Through Amazon with CreateSpace

As you know, Will It Fly? is self-published and printed on-demand through CreateSpace, a division of Amazon for print-on-demand books. If there’s a self-published paperback book for sale on Amazon, it’s likely due to CreateSpace.

The challenge was that I wanted to collect pre-orders as I see many authors do this on Amazon, but it’s not something that seemed possible when self-publishing and printing on demand with CreateSpace (now KDP). That is, until Azul, my accountability coach for this project, found out that it was possible by going through a completely wonky process that involved adding another arm of the Amazon branch, Amazon Advantage.

Amazon Advantage is a “self-service consignment program” that enables you to promote and sell media products directly on Amazon. It’s for publishers, music labels, studios, and authors. It gives you the tools you need to take advantage of the Amazon marketplace and help you with distribution and order fulfillment.

To share with you how wonky this process is, here’s the basic breakdown:

- Sign up with Amazon Advantage.

- Create a new item for your book and set the release date to your future publication date.

- Upload the cover image for your book. By now, you’ll have an Amazon page with the product displaying the future publication date. Pre-orders can now be placed.

- You’ll begin to get invoices for your book from Amazon. They’ll begin ordering copies from you and ask you to ship them in bulk to specific locations. Since you’re publishing through CreateSpace (now KDP) on-demand, you don’t have books to send anywhere, so you simply mark the items as backordered until that specific launch date.

- Meanwhile, you create your book on CreateSpace (now KDP) and fill in all of the necessary details (title, description, ISBN, categories, etc.) and upload the necessary files (book cover and manuscript). Don’t release it to the wild just yet though. Here’s where it gets weird.

- The evening before your launch, contact Amazon Advantage’s customer service team and tell them specifically to remove the item and transfer all of the pre-orders that came to CreateSpace (now KDP). They will then fulfill the orders that came in during the pre-sale.

- And then, magically on the backend, the Amazon page for your book switches from Amazon Advantage to CreateSpace (now KDP) fulfillment, and your book is live for customers to buy.

Here’s a link to a more detailed, step-by-step blog post where Azul and I first learned about the process. Eric, the main guy who shared this information with the community, also has a handy video that walks you through the entire process.

It’s wonky but it worked. By following all of the steps, we were able to pre-sell 3,110 copies of Will It Fly?, and those sales all dropped on February 1.

Why would you want to pre-sell your book?

Pre-sales for books are beneficial for a number of reasons:

- They help you build buzz before the book comes out.

- Leading up to the release date is a great time to offer bonuses for a limited time that help drive sales.

- It allows you to collect sales early for social proof.

- If done correctly, books will be reported as sold on launch day, which provides a massive bump in any potential bestseller list rankings.

The tricky part is the coordination of all of the moving pieces, especially when you’re self-publishing. When you work with a traditional publisher, they have relationships with the right people to make this all happen in a painless manner, and you likely won’t have to lift a finger to get it all set up.

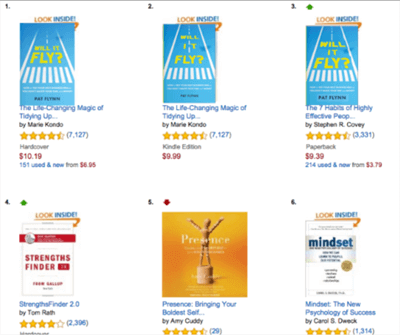

The other cool thing about the pre-sale process in Amazon is that you can climb the rankings of your book category during this time. Will It Fly? was released on February 1, but was available for pre-sales after putting it up on Amazon Advantage on January 23, and within a day after a few shares on social media and sharing it in the launch group, it jumped to number 637 overall.

On January 26, it shot up to number 163, and on January 27 it cracked the top 100 list, which was amazing. Also, because of its velocity, it was featured on the “Movers and Shakers” list, all before it even went live.

Was this important? Absolutely. Each milestone became another moment of excitement for me to share, which exposed the book even more. As people began to see it climb, more people began to purchase it.

Now, you maybe asking, what about the Kindle book?

Ah, the Kindle book. That’s a whole different story.

For now I’ll just say that we moved forward without the pre-sale for the Kindle book, and got it uploaded and ready for launch day on February 1 (more about this process in chapter 10 on book publishing mistakes because, well, if I could go back and do things differently, I definitely would have made sure we had more time to get the book ready for publishing).

Once the Kindle book was up and live it felt like a huge accomplishment and a relief, too, because it was such a long journey of hard work to get there. But that was only the beginning. There was still a lot more work to be done to promote and market the book and get it in the hands of the readers who it’s intended to help. We get into all of that in chapter 7 on how to market your book and chapter 8 on tips for marketing your book.

But first there are a few more things to consider, like what other options are there for getting a book published? And if you do choose the self-publishing path like I did, what does that mean for you, your book, your brand, and what all do you need to know? That’s coming up in the next chapter on how to start thinking about publishing your book.

How to Get Your Book Design Ready for Publishing

It’s design time! This is where you get to turn your book idea into a piece of art, one that will hopefully be marveled at by hundreds, thousands, or perhaps even millions of people! But how do you go from just a pile of text to a finished product? There’s a lot to know and digest when it comes to your book’s cover and interior design, so put on your seatbelt.

Designing a book is a holistic exercise in balancing multiple requirements, all of which affect one another; paper weight affects book size affects printing costs affects spine width affects cover design . . . you get the picture. As a result, it pays to brush up on what to expect before you dive in.

Your first step before proceeding any further is to find a designer! Do not DIY your book’s cover, unless you are yourself a skilled designer. And even if you are a skilled designer, your book cover design may be best handed over to another professional. As the author, you probably already have your hands full with the content production end of things. Plus, it can be helpful to outsource this portion of the book project to someone who’s not as close to the book as you are—fresh eyes and all that.

If you already have a designer who’s worked with you on other projects, like perhaps your website, then have a chat to see if they have experience designing books. Some designers are “cross-canvas” competent, but many aren’t, so be sure to verify before signing up to work with someone. If you end up working with your current designer or someone new, be sure to ask them to send you copies of books they’ve designed, so you can review them and determine if their style is up your alley and if they have the chops to pull it off.

Your Book’s Cover: First Impressions Still Come first